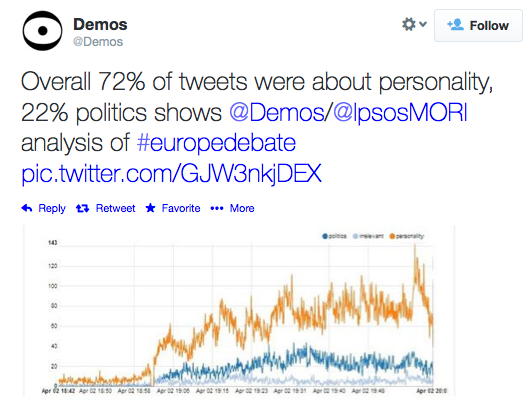

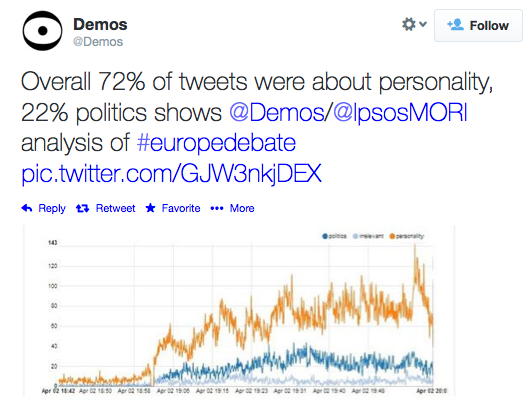

The televised Clegg-Farage debates on Europe [parts 1 and 2] provide a corpus of material to work with as we begin to test out ideas. Social media analyses, for instance, of the twitter stream, are being shared, such as this one from Demos which gives a very coarse grained classification of tweets as related to personality or politics:

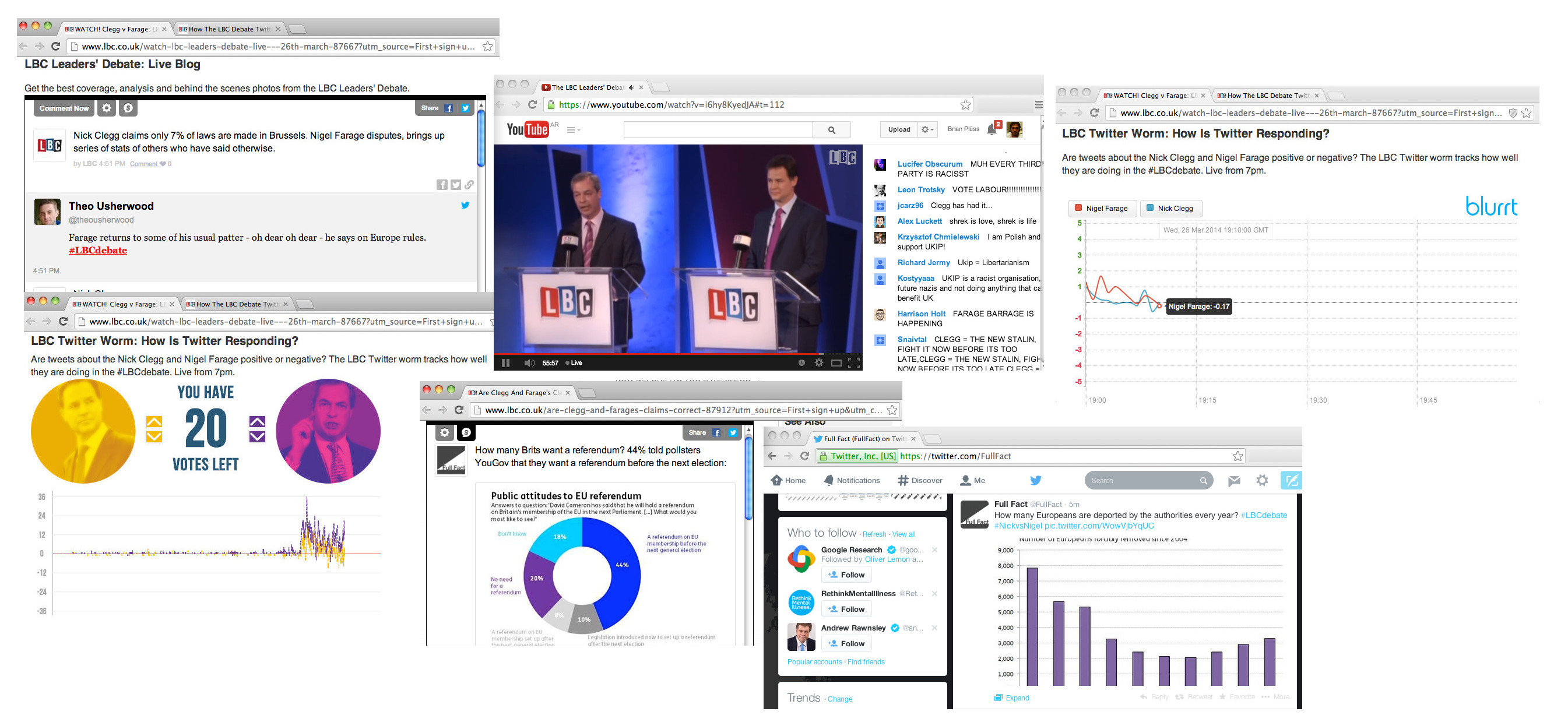

The media is saturated with commentaries on the personalities that came through, who had ‘won’, and in some cases, the quality of the debate. In KMi, we’ve started exploring reviewing how journalists are making sense of the debate, and we’ve begun mapping ideas.

If we take the second debate, one could simply map the transcript visually. However, this does not really add much value: the nodes are too large to reveal interesting structure:

What’s needed is a finer grained breakdown of the moves. In our 2010 General Election maps we did Dialogue Maps driven by the questions, and the order of contender responses. These were produced primarily in real-time, as the broadcasts went out, with minimal editing. They seemed, from informal inspection and feedback from others, to be useful in showing more clearly what happened in a given session.

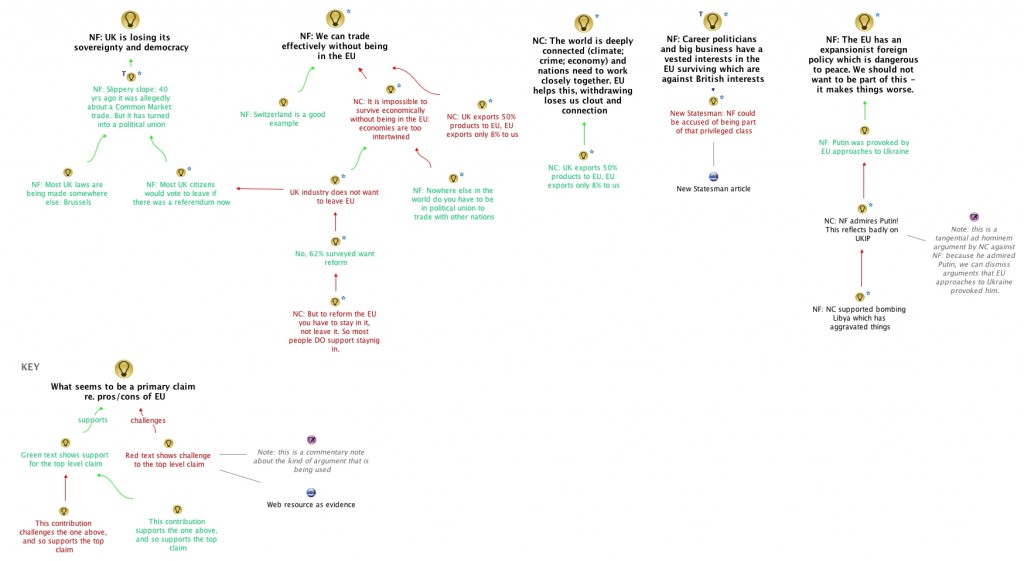

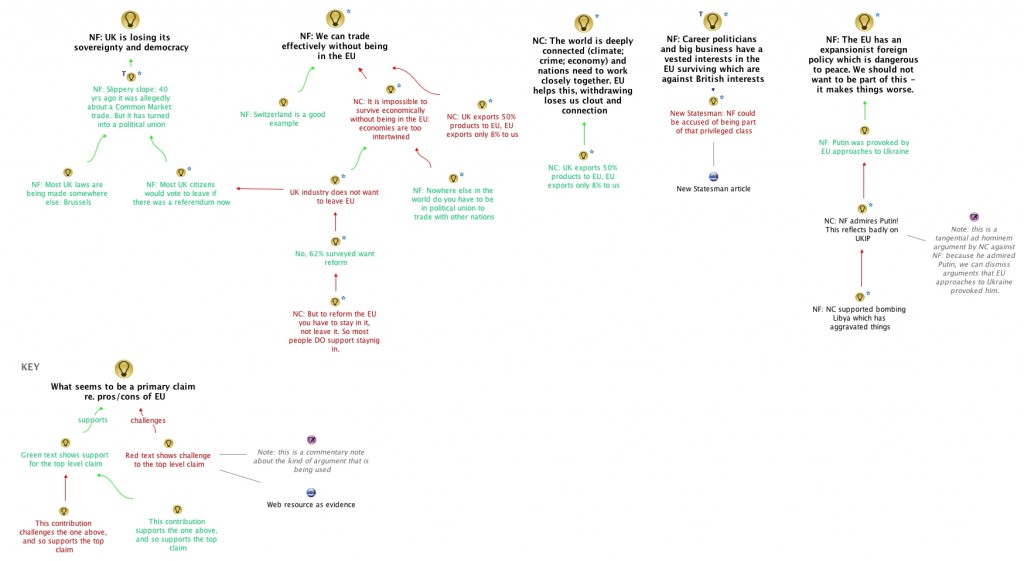

However, this time we’re aiming to do a more careful analysis. In this map, taken from the first 15mins of the transcript, we show which claims are being made and by whom (top), and who is supporting and challenging them. The order in which contributions were made is less influential, although can still be seen to some degree. The goal is to connect contributions as clearly as possible, so if Nick Clegg makes the same point three times, it might not appear as three nodes, but I might simply add quotations inside the detail of a summary node. See the Key at the bottom to read this map.

It’s not clear if we would want to render arguments like this to end-users, although feedback from the detailed focus groups run in January suggests that citizens would value ways to get an overview of such content. The first step is to understand what was going on in the debates, at least through this quite rational lens. (Screenshot below / Interactive Map)

More to follow!…

During the 2010 UK general election, the first ever televised Prime Ministerial debates took place. University of Leeds and KMi research investigated public reaction to these debates, the roles they may play in democratic engagement, and the potential of mapping the debates visually. In 2015 the next election is expected, providing the opportunity to investigate how new kinds of knowledge media can deliver completely new ways to replay the debates and engage with the arguments at stake.

During the 2010 UK general election, the first ever televised Prime Ministerial debates took place. University of Leeds and KMi research investigated public reaction to these debates, the roles they may play in democratic engagement, and the potential of mapping the debates visually. In 2015 the next election is expected, providing the opportunity to investigate how new kinds of knowledge media can deliver completely new ways to replay the debates and engage with the arguments at stake.